For recruiters, the right recruitment tech gives them a competitive advantage. However, the methods used to gather online data on potential candidates can raise legal and ethical questions around data ownership and fair recruitment practices.

In this blog post, we explain the difference between capture and scraping, and how recruiters can best navigate this online frontier.

Capture vs. Scraping

There’s no doubt that automating the process of extracting data about potential candidates or clients is a time-saver for recruiters. It’s a process that would otherwise be done manually, by transposing information from the source to a recruitment CRM or other data store.

From a recruiter’s perspective, what’s important is how that process is automated. This starts with knowing that capture and scraping are two very different approaches with very different implications.

- A capture tool processes information displayed to an authorized user of a service after downloading to the memory of their device.

- A scraping tool automates the download of prospective web pages directly to a database without user intervention.

Legally, this is yet to be codified, but ethically, the distinction is clear. A capture tool is designed to extract authorized information about a candidate from a source already accessible to the recruiter. Importantly, although it is automated, it still requires human direction and intervention. Essentially, capture is simply speeding up the manual copy/paste job that the recruiter would otherwise be doing.

On the other hand, scraping uses a ‘bot’ to indiscriminately extract candidate data from a website, which it may or may not be authorized to access. Authorization is largely determined by a data provider’s terms of service.

Terms Of Service

Put simply, some third-party terms of service distinguish between the use of legitimately downloaded information and the automated collection of information while others do not.

At the same time, some terms of service are so restrictive that they essentially disallow any use of information not explicitly approved by the vendor. It’s important to note that very few terms of service agreements are ever tested legally all the way to trial and damages.

Third-party vendors also have all kinds of enforcement mechanisms outside the legal system, which can influence customer behavior. Whether used systematically or on a whim, it’s possible for vendors to take a variety of actions to deter actual or perceived malpractice, including warnings, altering service privileges, suspending users, or even cutting them off entirely. They may also choose to engage with tool vendors.

Legal Cases

hiQ LABS v. LinkedIn (now owned by Microsoft) is one of the most high-profile cases on scraping to pass through the US legal system.

In 2022, the appeals court ruled that under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, anti-hacking law does not apply to public websites. So far, LinkedIn has been unable to obtain an injunction to stop hiQ from scraping personal data from its professional networking platform.

So far, the merits have not been decided. Although it outlines an interpretation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), the appeals court has suggested that the CFAA is not the correct law to regulate hiQ’s conduct.

So where does that leave recruiters? Automated methods for extracting candidate information are here to stay. It’s only a question of time before a court ruling sets the precedent for the legitimate and ethical use of these tools. For now, it’s up to recruiters to use capture tools in accordance with relevant data privacy laws — such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

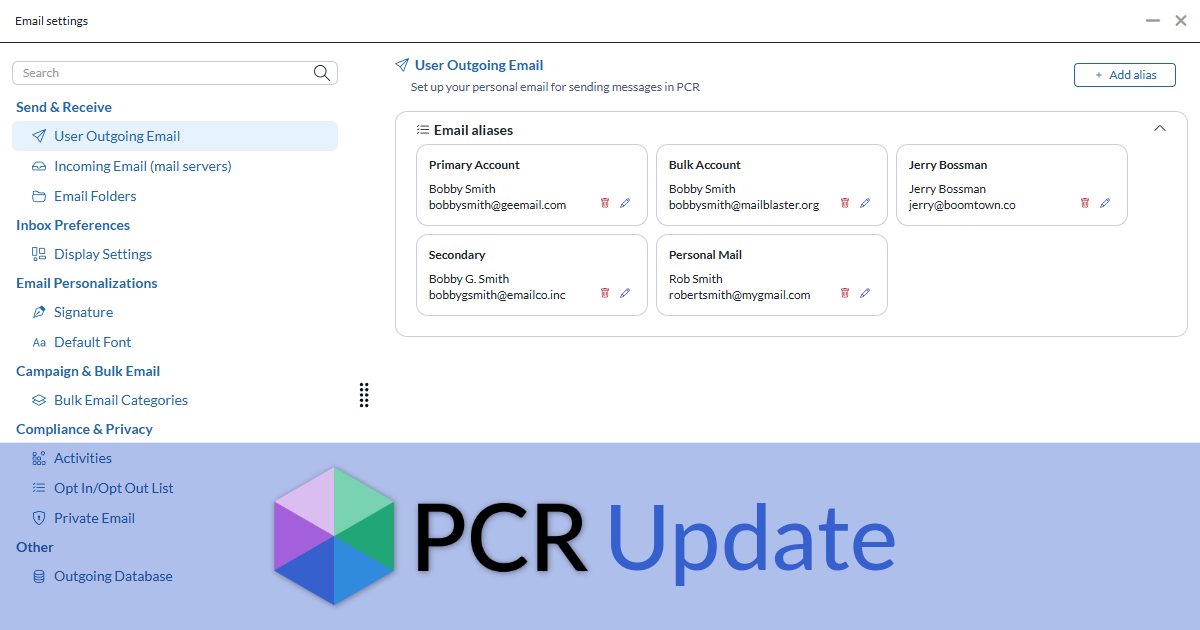

PCR Capture

As the name suggests, PCR Capture is a capture tool, not a scraping tool. As a specialist software vendor, its creator (Main Sequence Technology), has no measurable influence over major third-party service providers.

For that reason, we’re not able to certify any activity or obtain any kind of consent or waiver on behalf of our customers in their use of PCRecruiter Capture. Neither can we assume liability for behaviors and contexts over which we have no control.

However, we do assert a good faith belief that information downloaded to the memory of a user’s device in the normal and authorized course of the usage is information that belongs to the user, and the vendor has exhausted their right to that information by providing it.